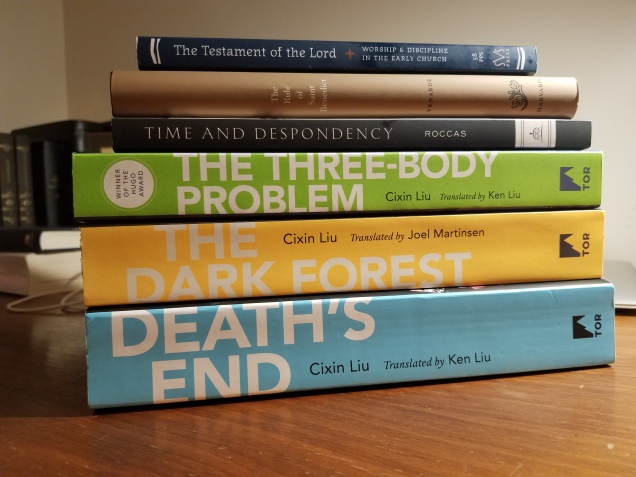

Here are the books I finished in July, with some notes. This was a good reading month. Continue reading

Here are the books I finished in July, with some notes. This was a good reading month. Continue reading

Languages

Of Doubt and Closed Doors

Today, on Thomas Sunday, we celebrate the “most wonderful doubt” of Thomas. As I discussed in my previous post, Thomas’s doubt is most wonderful because it is through this doubt that he comes to certain faith. For Thomas, it is the physical act of touching the body of the risen Christ that turns his doubt to faith and elicits the joyful confession: My Lord and my God!

This is all very well and good, but where does it leave us? What about our doubts? We certainly don’t have the advantage of following Thomas in seeing, speaking with, and touching the risen Christ. Continue reading

Something Greater is Here

![]() I recently hit Matthew 12 again in my daily Bible reading. This time around, I was particularly struck by Christ’s assertion—repeated three times in this chapter—that something greater is here. The latter two repetitions come in the context of the sign of Jonah:

I recently hit Matthew 12 again in my daily Bible reading. This time around, I was particularly struck by Christ’s assertion—repeated three times in this chapter—that something greater is here. The latter two repetitions come in the context of the sign of Jonah:

Then some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, “Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.” But he answered them, “An evil and adulterous generation seeks for a sign; but no sign shall be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the whale, so will the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth. The men of Nin′eveh will arise at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and behold, something greater than Jonah is here [καὶ ἰδοὺ πλεῖον Ἰωνᾶ ὧδε]. The queen of the South will arise at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for she came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon, and behold, something greater than Solomon is here [καὶ ἰδοὺ πλεῖον Σολομῶνος ὧδε]. (Mt 12:38–42) Continue reading

Chp 27 of the Rule of St Benedict & Trullo 102 on Penitential Discipline

As I continue my slow reading of the Rule of St Benedict, I was struck by chapter 27, “How the Abbot Should Care for the Excommunicated” (Qualiter Debeat Abbas Sollicitus Esse Circa Excommunicatos). In this context, “excommunication” has a technical meaning, which Benedict has laid out in the preceding chapters. Basically, “excommunication” means formally disciplining an erring brother who has already—unsuccessfully—been reprimanded twice privately and then once publicly (chp. 23; cf. Matthew 18:15–17).

As I continue my slow reading of the Rule of St Benedict, I was struck by chapter 27, “How the Abbot Should Care for the Excommunicated” (Qualiter Debeat Abbas Sollicitus Esse Circa Excommunicatos). In this context, “excommunication” has a technical meaning, which Benedict has laid out in the preceding chapters. Basically, “excommunication” means formally disciplining an erring brother who has already—unsuccessfully—been reprimanded twice privately and then once publicly (chp. 23; cf. Matthew 18:15–17).

The degree of this excommunication depends on the severity of the offense. Excommunication for a less serious fault means that he is deprived of table fellowship: he is to eat alone, after the rest of the brothers take their meals, and he should not lead psalms, antiphons, or readings in the oratory (chp. 24). However, a more serious fault carries a more serious degree of excommunication. In this case, the brother “should be banned from both table and oratory,” (suspendatur a mensa simul ab oratorio). He continues to eat alone, with the amount and time determined by the abbot, but his food is not to be blessed; moreover, none of the brothers should associate with him or speak to him, nor even bless him when they pass by (chp. 25). Brothers who associate with the excommunicated in anyway, without the abbot’s order, should themselves be excommunicated (chp. 26). The point of these measures is to bring the erring brother to his senses and lead him to repentance. Continue reading

On Remembering a Friend’s Suicide in the Light of the Resurrection

This morning, just before I went to Matins, I saw something on Facebook that reminded me that it was one year ago, today, that I learned someone I’d known from Columbus had committed suicide the previous night. Out of respect and concern for privacy, I won’t use her name here. This wasn’t someone from my parish community or my OSU department, and I can’t say that we were especially close, or even friends exactly, though I’ll refer to her as one. We had some mutual friends, and that’s how we became acquainted. But I had known her for several years, and while I lived in Columbus I saw her in person every once in a while, because I went to her for haircuts. Continue reading

St Benedict on Psalmody

I’ve been slowly working through the Rule of St Benedict in Latin, using the Dumbarton Oaks edition. Since in last night’s post on daily Bible reading I mentioned the Orthodox liturgical prescription of reading the Psalter in full once a week, it was interesting to come across the same principle in the Rule this morning. In chapter 18, Benedict lays out a detailed order for when specific psalms should be said in church. He then concludes:

“We urge this in particular: if this distribution of the psalms happens to displease someone, he should arrange it otherwise if he thinks it better, although in any case he must ensure that the entire psalter is sung every week, the full complement of 150 psalms, and is taken up again from the beginning at Sunday Vigils. For those monks who sing less than the entire psalter with the customary canticles in the course of a week show themselves lazy in the service of devotion, since what—as we read—our Holy Fathers energetically completed in a single day, we, more lukewarm as we are, ought to manage in an entire week.”

(Hoc praecipuae commonentes, ut si cui forte haec distributio psalmorum displicuerit, ordinet si melius aliter iudicaverit, dum omnimodis id adtendat ut omni ebdomada psalterium ex integro numero centum quinquaginta pslamorum psallatur et dominico die semper a caput reprendatur ad vigilas. Quia nimis intertem devotionis suae servitium ostendunt monachi qui minus a psalterio cum canticis consuetudinariis per septimanae circulum psallunt, dum quando legamus sanctos patres nostros uno die hoc strenue implesse, quod nos tepidi utinam septimana integra persolbamus. 18.22–24)

Continue reading